The American Railway system is almost as old as the country itself.

As early as 1809, a surveyor named John Tomson had drafted a layout for a “Tramroad” for his customer Thomas Leiper Esq. The survey was titled “Draft Exhibiting . . . the Railroad as Contemplated by Thomas Leiper Esq. From His Stone Saw-Mill and Quarries on Crum Creek to His Landing on Ridley Creek.”, and was the blueprint for, what many consider to be, the first American Railroad.

This is how the railroads began. Business owners created their own independent lines, connecting commodity hubs, like quarries and lumberyards, to job sites. This expedited their supply chains. During this period, “surveying and mapping activities flourished in the United States as people began moving inland over the inadequately mapped continent.” Once enough entrepreneurs had proven the effectiveness of their railways, the concept gained mainstream interest, and the maps mentioned above began featuring rail routes in their keys.

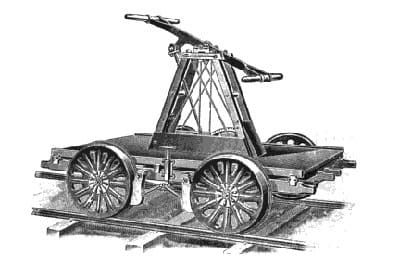

Old-Fashioned Handcars

The photo below features an old-fashioned handcar, also known as a pumper. It’s unlikely to surprise many a reader; it’s one of the many images that resonates with us as a symbol of the Westward Expansion, of Americana, of our past, but what may surprise you is their criticality in creating the Transcontinental Railroad.

The track was divided into “sections. ” These were typically about 6 to 10 miles long. Section Crews or Gangs maintained these sections. Each section typically had a section house, which stored a crew’s tools and, of course, their handcarts. An estimated 130,000 miles of track spanned America by 1900. With one handcar allocated per section, at minimum, an estimated 13,000 handcars would have been in operation, in the United States, at the time. This estimate obviously does not include spare carts, or the carts that comprised the telegraph fleets of companies like Western Union.

Engines Move Railway Car Innovation Forward

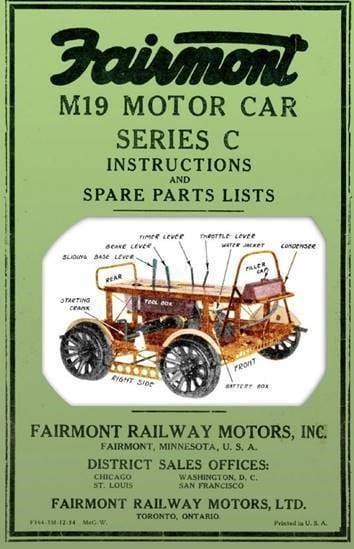

In tandem with time, innovation marched forward and brought us the internal combustion engine. Coupling engine power with the handcar birthed the early personnel carriers, which would come to be known as Motorcars. Railroaders called them “Speeders” because their speed surpassed the 10-15mph an industrious crew could generate pumping a handcar.

From the early 1900s to the 1980s, multiple companies like Beaver, Buda, Fairbanks-Morse, Kalamazoo, Tamper, Woodings, and Fairmont Railway Motors, Inc manufactured these speeders. Fairmont, acquired by Harsco Rail in 1979, was the undisputed king of the motorcars. The company initially manufactured cars with single-cylinder flywheel engines, A.K.A hit-and-miss engines. These cars were known as poppers, or putt-putts, due to the distinct cadence of their engine fire.

Soon, the modest 2-seater poppers were accompanied by larger gang cars, which, depending on how creative crews could get with their seating arrangements, could transport 6-8 men. Eventually, the single-stroke engine was swapped for a 16HP Onan CCKB Gas engine on the M-Series Cars, and Ford Diesels on the larger A-Series Gang Cars.

NARCOA, a national Speeder enthusiast group, has championed the restoration of these speeders. Most members try to stick with original parts, which are luckily available from Merchants like Phil Hopper. Supervised by railway personnel, NARCOA Members take these Speeders on Motorcar Runs. Keep an eye when traveling beside a railroad track; you may just catch a piece of history traveling beside you.

Hi-Rail Gear

Around the ’70s, companies like Harsco Rail popularized Hi-Rail Gear – the age of the hi-rail truck was born. Today, companies like RAFNA, DMF, Load King, & Continental Railworks have joined Harsco as Railgear OEMs.

Hi-Rail vehicles come in many different builds. Standard builds include pickup trucks, inspection vehicles, signal maintainers, service trucks, material handlers, welder vehicles, section trucks, and rotary dumps. These standardized builds will often have unique design features at the request of their end-user.

It is truly amazing to think of how far we’ve come and how far we’ll go – as an industry and as a people. Like our equipment, we are but the latest iteration of something greater. The newest face to a spirit that has existed for generations. We maintain the roads that bind us to our history, and we build paths to new horizons. We are railroaders.